Jessica Stoller on the Sévres Breast Bowl

Sévres Manufactory, design attributed to Jean Jacques Lagrenén. Breast Bowl, Service for the Rambouillet Dairy, 1787-88, Soft paste porcelain bowl and hard paste porcelain support, 12.5cm x 12.2cm x 13.3cm

The first time I saw the Sevres Breast Bowl was while paging through my dog-eared copy of An Illustrated Dictionary of Ceramics, a ceramophile’s compendium of obscure phrases, shapes, process and patterns spanning cultures and centuries. Under the “B”s, below “breakfast service” but before “brick” I came upon…

“Breast Bowl. A bowl in the form of, and moulded from a woman’s breast, the most famous example being that made for Marie Antoinette. It is a type of drinking cup, similar to the Greek MASTOS. The French term is bol sein."

I was immediately drawn in by this unknown object; despite its having been made in the 18th century, the piece appears totally contemporary to my eye. A sly play on a drinking vessel coupled with the mammary gland, the bowl is both elegant and unsettling.

The breast bowl also serves as a unique conduit from the 18th century back to antiquity. It draws its footless shape from the Greek form “mastos,” which translates to breast. The original shape created a challenge for the user. Tapering to a point, the cupped liquid must be consumed before the object is set down. Finished in a black figure ware style, mastos forms were often decorated with images related to Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and fertility, evoking ideas of frolicking satyrs, ritualistic drink and ecstatic dance.

It is interesting then to think what the original French designers were invoking when they circled back to this ancient form. The breast bowl was part of an elaborate porcelain set created by Sévres Manufactory specifically for Marie Antoinette’s dairy in Rambouillet. The historic phenomenon of the “pleasure dairy” was first created in the sixteenth century by Catherine de’Medici, another foreign born French queen who also had challenges producing an heir. The dairy she created allowed her to demonstrate her political agency while intertwining ideas related to femininity, nature and health. Not far from the city, the pleasure dairy allowed future aristocratic women to display their femininity and power in ways deemed more “correct” and palatable to the public, playing on age old themes of the connection between the female body and the pastoral landscape. The dairies embraced images of fecundity and nature, albeit a highly choreographed and sanitized version; meanwhile the real labor that kept this bucolic dream alive happened in an adjacent dairy.

Rumors linger that the breast bowl was allegedly molded on the Queen’s own breast. With that in mind, I can see the breast bowl as a symbol of the state harnessing female power for the greater “good” (producing an heir). It is also equally plausible to see this same object turn morbid within a few years as a sort of reliquary of the fallen Queen or, depending on your viewpoint, a fleshy token of her capriciousness. My Catholic upbringing also comes into view as I look at the breast bowl, echoes of St. Lucy or St. Agathe serenely offering severed body parts on silver platters come to mind. The female body becomes detached, tinged in equal measure with veneration and implicit violence.

Putting history and religion aside, this piece also taps into the mess of contradictions the female breast can enlist. A unique organ that can drip with sustaining and nourishing fluid, it is often dissociated from the body and fetishized to the point of absurdity. Many people squirm at the sight of a mother breast feeding, yet breasts unmoored from their biological function are in ads constantly, selling us anything and everything. The female breast is paradoxically highly visible and also unseen. #freethenipple.

Porcelain and breast milk have both been deemed golden for their monetary and nutritional worth, respectively. Eighteenth century Europe coveted rare and highly valued porcelain, also known as “white gold,” and colostrum, the substance (often yellow in color) that first appears when a woman (or mammal) is breastfeeding has been dubbed ''liquid gold” for the amount of antibodies that it contains. The porcelain Sévres Breast Bowl, perched atop its regal mammalian tripod, seems to glow with the hue of life, concentrated at the base in an amber-gold point.

I often think about how female bodies become the intersection between nature, culture, politics and religion. The Sévres Breast Bowl maps each of these onto its simple form resulting in an enigmatic work that continues to compel. Linking polytheistic Greece with revolutionary France, it reminds me that the breast is more than just anatomy; it attracts and repels, remaining innately powerful, provocative, and unmistakably political.

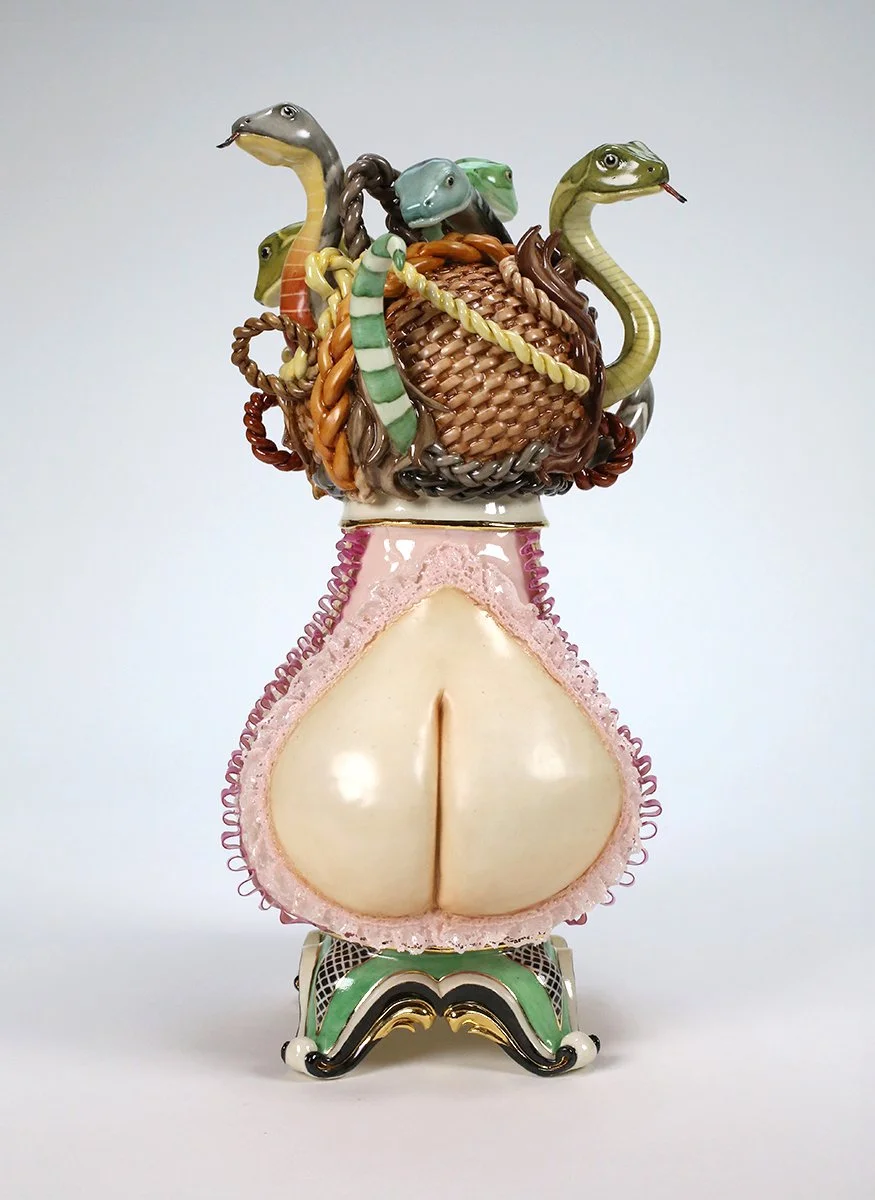

Jessica Stoller, Untitled (weave), 2015, porcelain, glaze, china paint, lustre, 12 x 6 x 7 inches

Jessica Stoller employs porcelain to create sculpture that balances the corporeal and the imagined, the idealized and the grotesque. Her works are complex, surreal hybrids, utilizing the historic language of porcelain and the still life, while creating new and unfamiliar forms that arrest the viewer’s eye with their beauty and abjection.